John Higgs is an author who has written books about such diverse subjects as the KLF and Timothy Leary. His most recent work seeks to make sense of the entire 20th century. In his story, John recounts why he chose to forego football in favour of exploring an imaginary castle.

John Higgs is an author who has written books about such diverse subjects as the KLF and Timothy Leary. His most recent work seeks to make sense of the entire 20th century. In his story, John recounts why he chose to forego football in favour of exploring an imaginary castle.

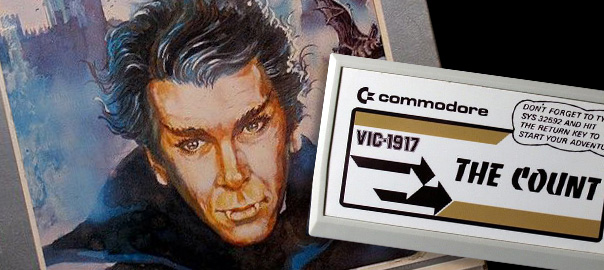

‘The Count’ by John Higgs

The Count was a vampire-based text adventure game from 1981, which I played on a VIC-20 computer. It came on a beige cartridge, because the computer itself only had 3.5kb of memory. Even with this cartridge, the game was sparse.

There were no graphics. There weren’t even any adverbs. The whole game took place by typing verbs and nouns. You started waking in a strange bed and, after getting up, you were told only that ‘I’m in a bedroom. Closed window. Brass Bed. North.’ This was Dracula’s Transylvanian castle as if described by someone hampered by the 140-character limit of Twitter. There were no evocative descriptions of the places you found yourself in, bar the absolute minimum information needed. So it might seem strange that, when I was asked to write about a childhood game, the first thing to jump to mind was The Count. Why did such a pared back game make such a strong impression?

Part of the reason is that the game trusted my imagination to fill in its gaps. By only telling me ‘You are in a bedroom’, or ‘kitchen’, or ‘dungeon’, I had no choice but to create those places yourself. Given the amount of time I spent wandering around that eerie, empty castle, my mental pictures of those rooms became sharp. Even now, that castle is more real and vivid to me than some of the houses I lived in during my twenties.

Part of the reason is that the game trusted my imagination to fill in its gaps. By only telling me ‘You are in a bedroom’, or ‘kitchen’, or ‘dungeon’, I had no choice but to create those places yourself. Given the amount of time I spent wandering around that eerie, empty castle, my mental pictures of those rooms became sharp. Even now, that castle is more real and vivid to me than some of the houses I lived in during my twenties.

Another reason was the importance of time. Every night you grew tired and fell asleep, only to wake drained of blood. You had three days to find and kill Dracula, or else you would become a vampire yourself. ‘It is getting dark’, the game would inform you after each turn, in what felt like a progressively hysterical manner. As night fell, a bat would flutter around, kept at bay only by the garlic you carried. This dreaded ticking clock created atmosphere.

The challenge of the game was not just figuring out how to kill Dracula. It was working out how to kill him in time. It required you to perform actions in a specific order, and calculating when to do things was as much a challenge as working out what to do. As text adventure games go, it was hard. The satisfaction of finally solving it, after many months of thought, was immense. My daughter was doing her GCSEs recently and asked me which exams I had passed. I genuinely couldn’t remember, but I can remember solving The Count. That was the real achievement of my childhood.

The Count was a puzzle box built in my imagination. Given the way that the timings of puzzles slotted together, I was inside a world that was evidently designed. It existed to challenge you. Your purpose inside that castle was clear: you had to solve the world. You can imagine its appeal to a 10-year-old boy growing up in North Wales in the early Thatcher years, where the real world was chaotic and the atmosphere considerably less evocative and heroic. I had the option of giving my attention to games like The Count, or to football. I still think I chose wisely.

The books that I write now are often puzzle boxes that I build in my imagination in an effort to solve the real world, so perhaps on some level I am still playing The Count. Our world appears chaotic, lacks a suitable level of romance, and shows scarce evidence of deliberate design. It does not appear to be a world which can be solved. Or perhaps, it may just be very hard. I still think attempting to solve it beats football.

To read more from John, follow him on Twitter, and if you would like to share your toy story, let me know @stuartwitts.